One of the lesser-known discoveries attributed to Pythagoras was that plucking two similar strings stretched to the same tension gave a pleasing sound if their lengths were related by simple integers (ie. whole numbers).

For example, if one string was half the length of the other (a 1:2 relationship) the result sounded quite nice. If the relationship was 2:3, that sounded pleasant too.

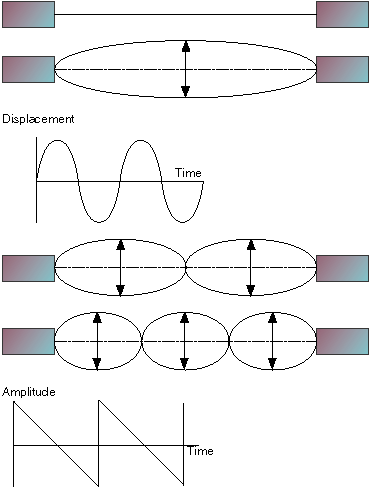

Let’s consider a stretched string that is fixed at both ends, but free to vibrate along its length. Figure 1 shows such a string at rest. Now imagine that we gently pluck the string exactly halfway between the ends. As you might imagine, this causes it to vibrate in the way shown in Figure 2. This is an example of a ‘standing wave’.

If the vibration (or ‘oscillation’) is as simple as that shown in Figure 2, a point at the centre of the string moves in a simple, repeating pattern called a sine wave (see Figure 3). We call this pattern the oscillation’s ‘waveform’, and the frequency with which the waveform completes one ‘cycle’ is called the ‘fundamental’ frequency of the string.

Imagine placing your finger in the exact centre of the string (but so that the string can still vibrate along its entire length) and plucking it on one side or the other. You can see from Figure 4 that a standing wave with half the wavelength of the original looks perfectly feasible.

Likewise, if you place your finger one-third of the way along the string, a standing wave of one-third the wavelength of the original should be possible (Figure 5) and so on.

Indeed, these standing waves can exist at all the integer divisions of the wave shown in Figure 2, and we call these the ‘harmonics’ of the fundamental frequency.

In all but some esoteric cases, the first harmonic (the fundamental, called f) is the pitch that you’ll perceive when you listen to the sound of the plucked string. The second harmonic (also called the first ‘overtone’) is half the wavelength of the fundamental and therefore twice the frequency. In isolation we would perceive this as a tone exactly one octave above the fundamental.

The third harmonic has a frequency of 3f (which is the perfect fifth, one and a half octaves above the fundamental) and the fourth harmonic, with a frequency of 4f, defines the second octave above the fundamental. The next three harmonics then lie within the next octave, and the eighth harmonic defines the third octave above the fundamental. And so it goes on…